I think that narration is one of the key principles of an effective networked workplace, or social business. Narration is making one’s tacit knowledge (what one feels) more explicit (what one is doing with that knowledge). Narrating work is a powerful behaviour changer, as long-term bloggers can attest. In an organization, narration can take many forms. It could be a regular blog; sharing day-to-day happenings in activity streams; taking pictures and videos; or just having regular discussions. Developing good narration skills, like adding value to information, takes time and practice. Narrating work also means taking ownership of mistakes.

Jane Bozarth discusses the nuts and bolts of narrating our work in this Learning Solutions Magazine article:

By sharing what we are doing and how we are learning, we distribute the tacit knowledge otherwise so hard to capture; invite feedback and encouragement from others; invite others to learn with us; document our work and learning for future use; and tie our learning to the efforts of others. Here’s a true story about physical rehab turned learning turned hobby turned community of practice turned two successful businesses, all via informal, social means. And all within six months.

The story that Jane tells happens outside the walls of an organization. I think this is important to note, because one of my other principles for an effective networked workplace is shared power. Shared power enables faster reaction times so those closest to the situation can take action. In complex situations there is no time to write a detailed assessment. Those best able to address the situation have marinated in it for some time. They couldn’t sufficiently explain it to someone removed from the problem if they wanted to anyway. This shared power is enabled by trust. Power in knowledge-based organizations must be distributed in order to nurture trust.

But sharing power is really difficult. In the video Dare to Disagree, via Jim Hays, Margaret Heffernan describes how people inside organizations, and professional communities, are afraid to challenge conventional wisdom, even when the data are overwhelming. The power structure exerts great pressure to conform. Only organizations that share power and encourage conflict can advance different ideas. As she says, “openness alone can’t drive change”.

Power-sharing decreases the fear of conflict. When those at the top hold most, or all, of the power, then those near the bottom will try to avoid conflict. But conflict is essential for learning. As Heffernan describes in the video, only in trusted relationships can conflict for learning happen. Sharing power creates trust.

Unfortunately, power is addictive. For example, simulations reveal that when there are no levels of hierarchy, everyone shares in the rewards of the system. When only one level level is added, then those at the top get 89% while those only one level down have to share the remaining 11%. No wonder hierarchies are so appealing. Power, and its effects on organizational performance, are holding us back. This is why we need to experiment with new and much flatter work structures.

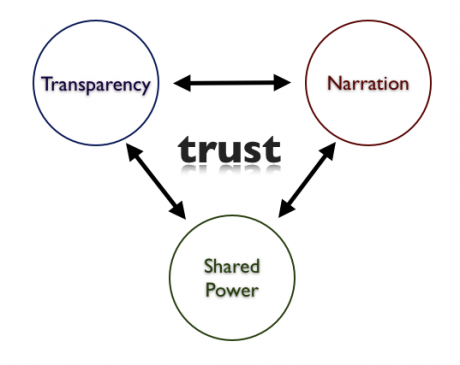

As Heffernan says, the truth will not set us free until we have the courage to use it. Our organizational structures, and their power systems, are a major part of the problem. Command and control are the barriers to an effective networked workplace. I have written that Enterprise 2.0 and social business are hollow shells without democracy because without power sharing, narration of work & transparency are a useless two-legged stool.

Nailed it …

This post condenses several years of brouhaha about collaboration, empowerment, top-down versus-bottom-up, etc. into what I suspect is still the reality on the ground in almost all organizations .. speaking up about something important, ‘telling the truth’ etc. will get your arse schlepped into a sling faster than you can shout “it’s not fair”. ;-)

Harold,

Brilliant post. These systems are broken and have been for some time…yet the magnetic pull of the hierarchy, as you note, is powerful and the hierarchy, in my opinion, ultimately serves to maintain its own existence. Many talented people wither in these systems …either becoming disengaged and simply accepting, rebelling and being discharged, or joining the ranks and serving to maintain the system. Good employees suffer under the weight of these structures; ultimately criticized and marginalized yet the power structure and system it condones continues unscathed. However I’m an optimist and believe that Wirearchy’s will work to deonstruct hierarchies morphing them into “ephemeral meritocracies” (HT Euan Semple).

Great post and wonderful video.

Kantor’s four-player model http://mitleadership.mit.edu/r-fpmodel.php suggests much the same. Wayyy back in the last century (1999) William Isaacs adapted and wrote about Kantor’s model http://www.dialogos.com/resources/files/systhink.pdf There’s an iPhone app just out also, the four-player model mini assessment, that I quite like.

I posted about one way of using the model and process http://thoughtstreamblog.ca/defining-team-roles-score-big-with-the-four-player-model/ It’s great to see this kind of thinking getting a bit more attention.

Another great resource supporting this is a book called The Opposable Mind by Roger Martin.

I do have a question, but it related more to your last post on complexity so will ask it there.

jamie

I am not disagreeing with the diversity that Margaret suggests, but I might take issue with (as in, it still needs more attention) seeking out people who are different than us. This is a hugely over-simplified statement, because the example that she offered of the two who were collaborating together did not support such a view at all. The subtleties are critical. The two individuals working together were working toward a common cause — to find the truth. They had a mutual respect for using evidence to guide them. They ‘agreed’ to approach this common cause from entirely different perspectives.

The main point is, there are a lot of people who are ‘different’ than us who would not be amenable to pursuing a common cause and being willing to do so from entirely different perspectives.

I agree, Paula, sharing complex knowledge requires strong social ties (trusted professional relationships). Our networks should be diverse but you can’t do real work, like structured projects, with a diverse group that has weak social ties.