“The basic unit of social business technology is personal knowledge management, not collaborative workspaces.” —Thierry de Baillon

Personal knowledge management (PKM) is a set of processes, individually constructed, to help each of us make sense of our world and work more effectively. But what we loosely call knowledge, using terms like knowledge-sharing or knowledge capture, is often just an approximation. As knowledge management expert Dave Snowden says, we are not very good at articulating our knowledge; “We always know more than we can say, and we will always say more than we can write down.” [see comment by Cynefin co-author, Cynthia Kurtz]

Knowledge

When we use our knowledge to describe some data, such as what we remember from an experience or our summary of a book, we convey this knowledge by creating information, even though writing it down is not perfect. This does not mean that we shouldn’t even try, because the cumulative pieces of information, or knowledge artifacts, that we share can help us have better conversations and increase our understanding of things that cannot easily be codified. Our individual sense-making can be shared, and from it can emerge better organizational knowledge. This is not a linear process, as in from information we get knowledge, which over time becomes wisdom. Gaining knowledge is much messier than that.

Becoming knowledgeable can be thought of as bits of knowledge partially shared and experienced over time. It is laborious, hence the reason why masters through the ages could only have a limited number of apprentices. But when writing, and later books, came along, we had a new technology that could more widely distribute information created by the wise, and also the not so wise. Whether being mentored by a master or reading a book, knowledge does not actually get transferred, but shared observations and information can be helpful to those who have a desire to learn and do something with their learning.

Merely being well read is not enough to be knowledgeable, as possibly first noted by Socrates. Plato wrote in Phaedrus that Socrates felt the written language would result in “men filled, not with wisdom, but with the conceit of wisdom, who will be a burden to their fellows“. Socrates saw a core truth in learning from artifacts like books. Even today, we cannot become complacent with knowledge and just store it away. It has a shelf life and needs to be used, tested and experienced. It should be shared amongst people who understand that they are only seeing a fragment of others’ knowledge. Because it is so difficult to represent our knowledge to others, we have to make every effort to continuously share it. Once is not enough, as most parents know. Knowledge shared in flows over time can help us create better mental pictures than a single piece of knowledge stock, like a book, can ever do.

Seek : Sense : Share

Capturing knowledge, as crudely as we do, is just a first step. The PKM framework I have developed over the past eight years suggests two more steps: sense-making and sharing. PKM, or learning in networks, is a continuous process of seeking, sensing, and sharing.

Seeking is finding things out and keeping up to date. Building a network of colleagues is helpful in this regard. It not only allows us to “pull” information, but also have it “pushed” to us by trusted sources.

Sensing is how we personalize information and use it. Sensing includes reflection and putting into practice what we have learned. Often it requires experimentation, as we learn best by doing.

Sharing includes exchanging resources, ideas, and experiences with our networks as well as collaborating with our colleagues. As Tim Kastelle notes:

Yes, when we send our ideas out into the world, they change the people with whom they interact.

But sending these ideas out, and seeing how they interact with people changes us as well.

Innovation

Scott Anthony, author of The Little Black Book of Innovation, identifies four skills exhibited by innovators: Observing; Questioning; Experimenting; Networking. These directly align with the PKM framework of Seek, Sense, Share. It is quite likely that innovation in organizations can be improved with individuals practising PKM. It could even be a major value proposition for Learning & Development departments everywhere, something to seriously think about.

Seeking includes observation through effective filters and diverse sources of information. Sense-making starts with questioning our observations and includes experimenting, or probing. Sharing through our networks helps to develop better feedback loops. In an organization where everyone is practising PKM, the chances for more connections increases.

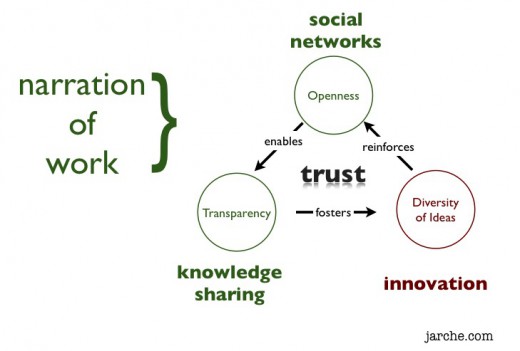

PKM may be an individual activity but it is also social. It is the process by which we can connect what we learn outside the organization with what need to do inside. Research shows that work teams that need to share complex knowledge need tighter social bonds. Work teams often share a unique language or vocabulary. However, they can become myopic and may lack a diversity of opinions. Social networks, on the other hand, encourage diversity and can sow the seeds of innovation. However, it is almost impossible to get work done in social networks due to their lack of structure. PKM is the active process of connecting the innovative ideas that can arise in our social networks with the deadline-driven work inside organizations.

PKM is beneficial on both a personal and organizational level, but its real value is in increasing innovation. Without innovation, organizations cannot evolve.

Social Learning

Both collaborative behaviours (working together for a common goal) and cooperative behaviours (sharing freely without any quid pro quo) are needed in the network era. Most organizations focus on shorter term collaborative behaviours, but networks thrive on cooperative behaviours, where people share without any direct benefit. PKM helps to add cooperation to workplace collaboration.

In addition to seeking, sensing and sharing, we need to become adept at filtering information as well as discerning when and with whom to share. Like any skill, these require practice and feedback. Much of this feedback can be provided in communities of practice, a half-way space between work teams and social networks, where trusted relationships can form that enable to share more openly.?

Connecting social networks, communities of practice and work teams, becomes an important framework for integrating learning and working in the network era. We seek new ideas from our social networks and then filter them through more focused conversations with our communities of practice, where we have trusted relationships. We make sense of these embryonic ideas by doing new things, either ourselves, or with our work teams. We later share our creations, first with our teams and perhaps later with our communities of practice or even our networks. We use our understanding of our communities and networks to discern with whom and when to share our knowledge.?

Narration

Narrating one’s work does not get knowledge transferred, but it provides a better medium to gain more understanding. Working out loud is a concept that is very easy to understand, but not quite so easy to do. Most people are too busy managing in their information age workplaces and have little spare time to try to learn how to work in the network age. The most important step in learning a new skill is the first one. This same step has to be repeated many times before it becomes a habit.I have learned that the first step of starting to work out loud, as part of personal knowledge management, has to be as simple as possible. Here are three simple steps I recommend to begin a regular PKM practice with.

1) Free Your Bookmarks: This is a very simple shift that only requires a slight deviation from a common practice: saving bookmarks/favourites on your browser. Using tools like Diigo, or Delicious moves them off a single device, makes them more searchable, and (later) makes them shareable. Being able to share is usually not a prime reason why people start using social bookmarks but it becomes more important over time.

2) Aggregate: Driving as many information sources as possible through a feed reader such as Google Reader or Feedly, saves time and helps stay organized. It is amazing how many people still do not understand RSS or how to grab a feed and save it. Aggregation makes information flows much easier to deal with.

3) Connect: How does one get started micro-blogging on a platform like Twitter? I suggest beginning with an aim in mind, such as professional development or staying current in a specific field. The search function can help find people who post about a specific topics. To start, one should follow no less than 20 and no more than 30 interesting people. Once set up, beginners should dip into their stream once or twice a day and read through any posts of interest. Over time, as they follow links, they may add or delete feeds. Within a week or two, anyone should be able to sense some patterns and then modify their streams to provide more signal and less noise.

Sometimes we get all caught up in the latest social media tools. Getting started working out loud is not complicated and should not involve a steep learning curve on a complicated system. It is best to start with simple tools and frameworks.

Small pieces, loosely joined

The mainstream application of knowledge management and learning management over the past few decades has had it all wrong. We over-managed information, knowledge and learning because it was easy. Our organizations remain enamoured with the next wave of enterprise software systems. But the ubiquity of information outside the organization is showing the weakness of centralized enterprise systems. As organizations begin to understand the Web, the principle of “small pieces loosely joined” is permeating some thick industrial age walls. More workers have their own sources of information and knowledge, often on mobile devices, but they often lack the means or internal support to connect their knowledge with others to actually get work done. Supporting PKM, especially internal sharing, can help information flow more freely.

Personal knowledge management frameworks can help knowledge workers capture and make sense of their knowledge. Organizations should support the individual sharing of information and expertise between knowledge workers, on their terms, using PKM methods and tools. Simple standards like RSS can facilitate this sharing. Knowledge bases and traditional KM systems should focus on essential information, and what is necessary for inexperienced workers. Experienced workers should not be constrained by too much structure but rather be given the flexibility to contribute how and where they think they can best help the organization.

We know that formal instruction accounts for less than 10% of workplace learning. The same rule of thumb should apply to knowledge management. Capture and codify the 10% that is essential, especially for new employees. Now use the same principle to get work done. Structure the essential 10% and leave the rest unstructured, but networked, so that workers can group as needed to get work done. Teams are too slow and hierarchical to be useful for the network era. Organizations structured around looser hierarchies and stronger networks are much more effective for increasingly complex work.

Conclusion

PKM is a framework for individuals to take control of their professional development while working in organizations or across networks. Disciplined personal knowledge management brings focus to the information sea we swim in. The multiple pieces of information that we capture and share can increase the frequency of serendipitous connections, especially across disciplines and outside organizations. As Steven Johnson, author of Where Good Ideas Come From says; “chance favors the connected mind“.

An artisan is a skilled worker in a particular craft, using specialized processes, tools, and machinery. Artisans were the dominant producers of goods before the industrial era. Today, knowledge artisans of the network era are using the latest information and social tools in an interconnected economy. Look at a web start-up company and you will see it is filled with knowledge artisans, using their own tools and connecting to outside social networks to get work done. They can be programmers, designers, writers, or any other field requiring complex skills and creativity. One of their distinguishing characteristics is the ability to seek and share information with their networks in order to get work done. Knowledge artisans are connected workers.

An artisan is a skilled worker in a particular craft, using specialized processes, tools, and machinery. Artisans were the dominant producers of goods before the industrial era. Today, knowledge artisans of the network era are using the latest information and social tools in an interconnected economy. Look at a web start-up company and you will see it is filled with knowledge artisans, using their own tools and connecting to outside social networks to get work done. They can be programmers, designers, writers, or any other field requiring complex skills and creativity. One of their distinguishing characteristics is the ability to seek and share information with their networks in order to get work done. Knowledge artisans are connected workers.